Imagine you are a nurse working in a busy public hospital. You’re preparing for open heart surgery scheduled to occur in just one hour, and the surgeon needs to know the patient’s medical history. You go to the computer to pull up the files, but something is awry. Instead of the Microsoft Windows interface you were expecting, the message below is displayed:

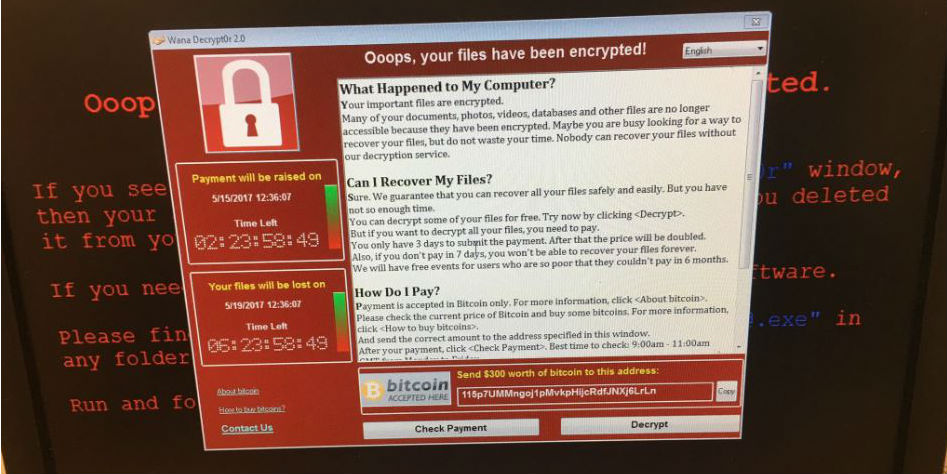

“Oops, your files have been encrypted!” reads the bizarre statement. After demanding payment to decrypt your files, the message requires that $300 in Bitcoin sent to a web address composed of a seemingly random string of letters and numbers. Adding to your stress, a countdown clock on the left side of the screen tells you that the price of decryption will go up in 2 days, 23 hours, and 58 minutes. Another countdown clock tells you that all of your files will be lost within one week if you do not pay.

How would you react in this situation? What would you tell the surgeon expecting to operate? What would you tell your supervisor? Would you pay the ransom? If not, what would you tell the patient?

While a version of this scenario was recently a central plot in the popular television drama Grey’s Anatomy, this was the actual situation facing many medical personnel in British National Health Service (NHS) hospitals earlier this year. On Friday May 12, the WannaCry ransomware cryptoworm affected forty-eight hospitals across the NHS system. One man expecting to have heart surgery expressed great surprise after being told that his operation was being cancelled due to the cyberattack. Others patients were turned away when a hospital announced that all computers would be down for the weekend because patient files could not be accessed.

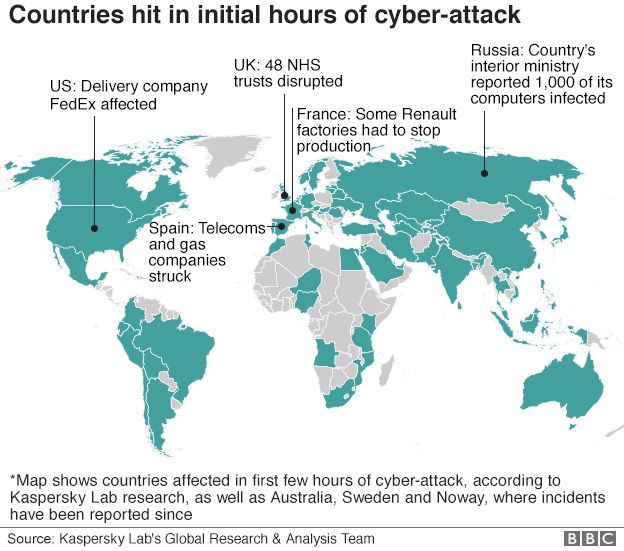

As May 12 wore on, it became clear that the NHS was not the sole target of the ransomware attack. The WannaCry worm affected at least 75,000 computers in 99 countries. The French automobile manufacturer Renault was forced to shut down production. The attack also affected trains in Germany, gas utilities in Spain, and FedEx offices in the United States. British Prime Minister Theresa May released a statement declaring “This is not targeted at the NHS, it’s an international attack and a number of countries and organizations have been affected.” Europol similarly described the attack as a global disruption that was “unprecedented.”

Hospital systems are central to a city’s function, providing healthcare for diverse populations in urban centers all over the world. Cyberattacks on these systems can cripple an entire city. In the case of the WannaCry attack, this appears to be the goal. On Monday, December 18th 2017, the US and UK definitively attributed the WannaCry attack to North Korea which intended “to cause havoc and destruction.” The sheer scope of the WannaCry attack shows the frightening vulnerability of critical urban infrastructure to cyberattack. MacAfee declared WannaCry part of a growing class of attacks called pseudo-ransomware. WannaCry only collected about $150,000 in ransom, as opposed to other ransomware’s larger paydays. When a security researcher asked the WannaCry support team why the ransom payment requested was so low, “the ransomware support representative told her that those operating the ransomware had already been paid by someone to create and run the ransomware campaign to disrupt a competitor’s business”.

During the WannaCry attack, it was possible for the victims to interact with the perpetrators’ support operations. This provided a perfect opportunity to deploy a defensive social engineering technique like cyber negotiation. Because the ransomware operators were apparently being paid by North Korea, they had little incentive to extract additional money from the victim. This information could have been used to negotiate the release of the hostage data without serious financial losses to the victim. If the goal was to cause disruption, a victim could claim that WannaCry had already succeeded, disrupting their business and leading to a “Good for You, Great for Me” scenario: the operators might have been convinced that they had achieved their primary purpose while the victims might have been able to accomplish their overriding goal which was to retrieve their data unharmed and resume hospital services.